What To Do If You See a Violent Police Arrest

On July 23, 2016, Abdirahman Abdi was beaten into unconsciousness and killed during his arrest by Ottawa police officers following allegations of sexual harassment at the Bridgehead coffee shop in the Hintonburg neighborhood of Ottawa.

On July 23, 2016, Abdirahman Abdi was beaten into unconsciousness and killed during his arrest by Ottawa police officers following allegations of sexual harassment at the Bridgehead coffee shop in the Hintonburg neighborhood of Ottawa.

The case of Abdi Abdirahman will be investigated by the Special Investigation Unit (SIU) to assess whether there was police wrongdoing on the part of the Ottawa Police Service in his arrest and death. The outcome of the investigation will be determined by the evidence available and the circumstances and rigor of the investigation itself. But that should not be the end of the inquiry. The use of police violence is reasonable and necessary to the extent that society explicitly or tacitly accepts that such violence is a required corollary of peace and does not bring the system of administration of justice into disrepute. As concerned citizens of the Ottawa community, through this incident, our collective conscience spurs us to contemplate whether the force used by police in such situations should be condoned. Such an inquiry may shine a light on the structural realities of the policing of marginalized communities – involving race, poverty and mental illness.

Police officers will continue to make good or bad judgment calls in effecting arrests and the Courts will continue to apply after-the fact methods of assessment to determine what happened. But the political and social utility of this use of force is not inevitable, it must be controlled and curtailed by informed, compassionate and socially responsive debate and action.

Here are four considerations to bear in mind if you encounter a situation where you believe that excessive force is being used by the police.

Firstly – if you do take videos of police arrests and violent confrontations, preserve this information on your phone or mobile device. In Canada it is not a crime to photograph the police. You are not obliged to provide your phone to the police; however, you may be cautioned that you are not to destroy the recording on your phone, which may constitute evidence of a crime or evidence related to a criminal investigation. An officer is not permitted to seize your cell phone and/or delete your video. If an officer questions you about the content of your cell phone, you can volunteer to view the evidence with the officer or go to the police station to provide a copy of the evidence. If there is no risk of imminent destruction of the evidence, there is no reasonable basis for police to take measures to seize your property without a court authorized warrant. Your own personal information on your phone apart from arrest video – along with your photos, contacts, other videos, texts and emails - remains your private property and should not be seized or copied by the police.

Secondly, it is not illegal to post your video to social media or to distribute it to the news media. This is a personal choice you must make on your own in the circumstances; however, in doing so, you should be aware that the public disclosure of the information may identify you as a material witness and you may be called as a witness in a criminal investigation for the prosecution or the defense to confirm that you recorded the video, the circumstances of the recording and whether the video was altered or changed in any way.

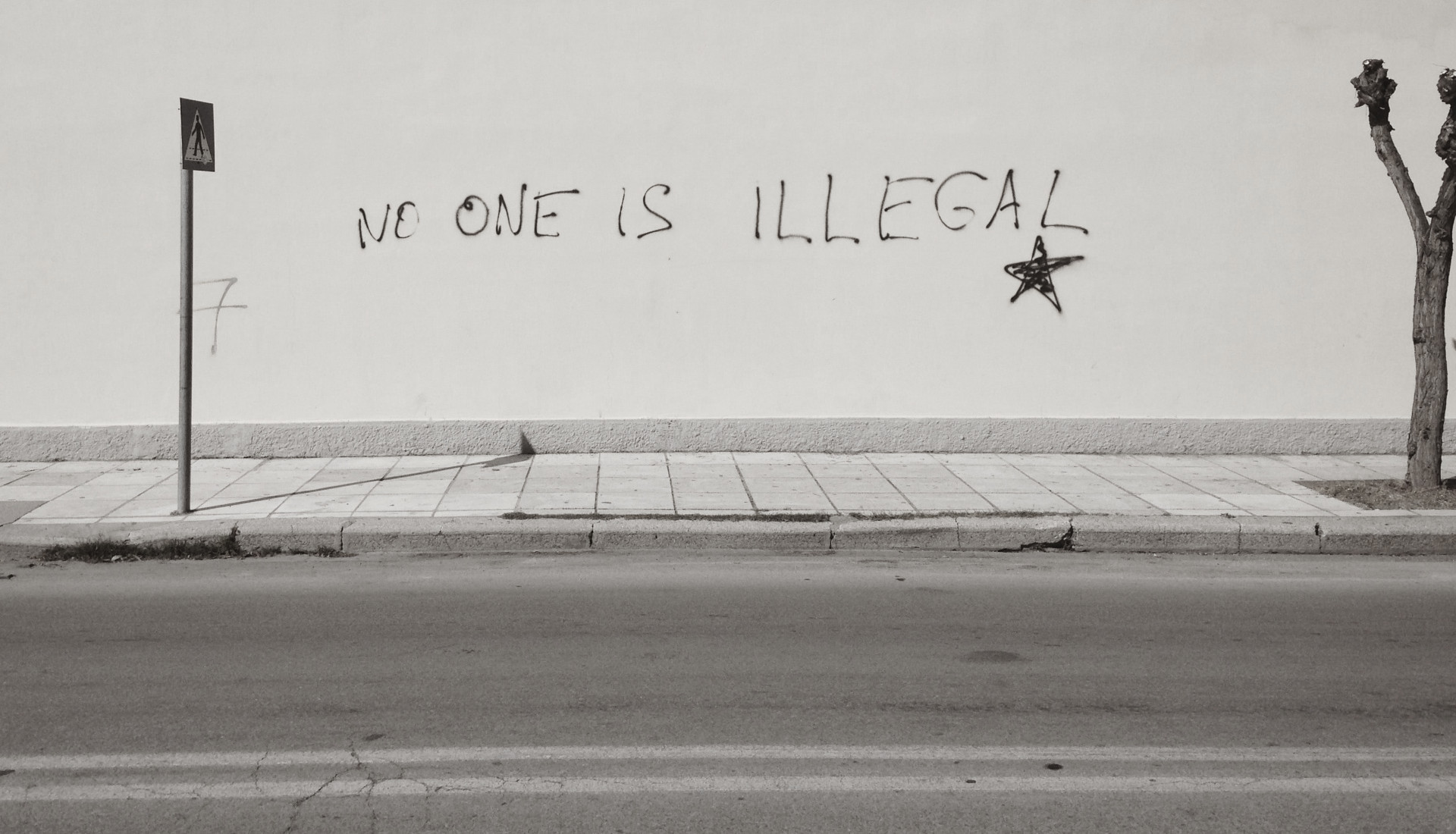

Thirdly, it is okay to be critical of the police. By criticizing police action, you should be mindful of not inciting violence or specific crimes against any person or the police themselves. Open and critical discussion is part of responsible democratic discourse that is protected under section 2(b) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and is something that the state, including the police, are required to protect. Many police officers themselves critical of police practices; however, there is an institutional tendency on the part of police chiefs and public messaging to defend police action in an attempt to promote respect for the Rule of Law. Respectful discussion, however, does not mean that citizens are required to respect the rule by law and live in a culture of fear, but rather, we should be alive to the importance of raising structural issues regarding policing in public forums and to organize in solidarity with communities which find themselves disproportionately policed.

Fourthly, people should be aware that policing as a public service, in addition to being regulated by individual civil liberties protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is also governed by human rights laws in Canada. This means that racial profiling or policing based on color is a violation of the Ontario Human Rights Code. Likewise, policing that fails to reasonably accommodate a person’s disability is also a violation of the Code. Although, it is difficult to calibrate how human rights accommodation should be implemented in the context of a dynamic arrest situation, we must strive to put in place systemic safeguards that provide specialized training, alternative force continuum models, multidisciplinary emergency response teams working alongside and within police forces and police forces that are reflective of the demographic make-up of the communities that they serve and protect. Individual police officers may be held responsible for the violence that they perpetrate in arrests, but the source of the problem is not embedded in the moral blameworthiness of officers, it is a cultural problem that requires a fundamental rethinking of the way that “the peace” is defined and the policy choices that are made to defend this peace through our state institutions.